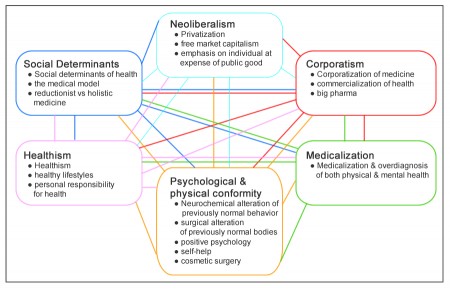

Continued from parts one and two, where I defined the terms used in the following diagram of my blogging interests. Click on the graphic for a larger image.

If I had written the previous two posts a year ago, I would have realized how much my interests were intertwined. I guess I wasn’t ready to do that. Anyway, in this post I catalog some of the connections.

Healthism

~ Healthism and psychological and physical conformity: Healthy lifestyle campaigns promote an ideal way of life that encourages individuals to alter their behavior and appearance. Although it’s true that we would all be better off if we didn’t smoke, that doesn’t make anti-smoking laws any less authoritarian, i.e., requiring conformity (see the section on anti-authority healthism in this post). The fitness aspect of healthy lifestyles promotes the desirability for both men and women of acquiring (i.e., conforming to) specific body images.

“Self-help is the psychiatric equivalent of healthism.” That’s a slogan I made up. I’m not sure yet if it will stand up to scrutiny. Certainly the self-help industry encourages self-criticism, which leads to a preoccupation with those aspects of personality currently considered undesirable.

~ Healthism and medicalization: Once a bodily process or characteristic has been labeled a medical condition, the ensuing publicity (advertisements, news stories) encourage us to be concerned (anxiety healthism). This increases our willingness to seek and agree to medical treatment, which can lead to overdiagnosis.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) ads for pharmaceuticals increase our anxiety about previously normal behaviors and diseases we do not (yet) have, increasing both healthism and overdiagnosis. Disease mongering only works if it can generate anxiety healthism. The promotion of personal responsibility for healthy lifestyles encourages us to seek medical attention even in the absence of symptoms. This also contributes to overdiagnosis.

~ Healthism and corporatism: The sale of health goods and services, especially under the guise of healthy lifestyles, is highly profitable. Since it’s easy to create anxiety about health and often quite difficult for people to change their health behaviors, this is a market with seemingly infinite potential (featured in book’s like The Wellness Revolution: How to Make a Fortune in the Next Trillion Dollar Industry). Once health and health care are controlled by financial interests, there is strong motivation to increase consumption, hold individuals responsible for healthy lifestyles, and encourage healthism.

~ Healthism and neoliberalism: Healthism, healthy lifestyles, and personal responsibility for health focus attention on the individual. This obscures and distracts from the social conditions that contribute to disease. This strategy is a core tenet of neoliberalism. “[I]ndividual responsibility as ideology has often functioned historically as a substitute for collective political commitments.” (Crawford)

~ Healthism and social determinants of health: Health policies that emphasize healthy lifestyles and personal responsibility for health are based on the assumption that health and disease are under the individual’s control. This works against a broader understanding of the role of social determinants of health. “Individualism … looks to change individual behavior, not the conditions that give rise to inequalities.” (Hofrichter)

Psychological and physical conformity

~ Conformity and medicalization: Medicalization is a prime mechanism for promoting psychological and physical conformity. Can you say ‘deviance’? Are you ‘at risk’?

~ Conformity and corporatism: Surgically altering one’s appearance (e.g., designer feet) presumably increases one’s chance of success in a society that commodifies bodies (i.e., in a society where salary, career advancement, social status and marriage prospects are influenced by appearance). Altering one’s personality with psychopharmaceuticals allows one to project the qualities necessary for success in a highly competitive society.

Another slogan: “Cosmetic surgery is the physical equivalent of ‘better than well’ psychopharmaceuticals.”

~ Conformity and neoliberalism: Although neoliberalism emphasizes the ideology of the individual, it does not advocate broadening the definition of normal. Economies work best when individuals conform to the dominant ideals of society. Increasingly this conformity can be aided by medical intervention (psychopharmaceuticals, cosmetic surgery, weight loss surgery).

Another connection, pointed out by Barbara Ehrenreich: Positive thinking promoted by self-help gurus is a useful way to blame the individual for “the crueler aspects of the market economy.”

~ Conformity and social determinants of health: Medical efforts that help the individual conform to cultural norms – both psychological and physical — involve identifying and altering characteristics that are unique to the individual. Whether it’s the neurochemistry of an individual’s brain or the modification of a body part, these efforts are examples of reductionism and the medical model. The focus on the individual ignores and leaves unquestioned the social environment that establishes the norms. Rather than ask how the environment (social, economic, physical) could become more conducive to health, medical intervention allows individuals to accommodate themselves (conform) to the existing environment.

Medicalization

~ Medicalization and corporatism: One of the drivers of overdiagnosis is the desire to increase revenue (e.g., physician remuneration based on pay-for-service, where services typically include screenings that lead to overdiagnosis).

As I discussed in part one, the pharmaceutical industry increases profits by engaging in disease mongering. Patient populations are expanded by redefining a condition (ED) or lowering cut-off points (diabetes, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, high cholesterol level).

~ Medicalization and social determinants of health: Many examples of medicalization (e.g., lowering cut-off points) emphasize individual risk and risk prevention — a feature of the medical model. The primacy of the medical model in health policy decisions means that modifications of existing health care systems receive much greater consideration than social determinants of health.

Corporatism

~ Corporatism and neoliberalism: Neoliberal policies – free trade, deregulation, supply-side economics – favor corporate interests over the public good.

Mitt Romney’s business career exemplifies the influence of neoliberalism on corporations. His consulting firm, Bain Capital, was influential in the evolution of corporate values from a broad set of responsibilities to an exclusive focus on share-holder profits. (See an excellent article on this here.)

~ Corporatism and social determinants of health: Corporate interests emphasize short-term profits at the expense of public health. They also create externalities (side-effects such as environmental pollution) that often affect the economically disadvantaged disproportionately.

Neoliberalism

~ Neoliberalism and social determinants of health: Neoliberalism seeks to eliminate government policies that promote greater equality (especially welfare policies). This exacerbates health inequities. Greater inequality in turn undermines the social infrastructure, which contributes to a loss of social cohesion. (Coburn (PDF)) A society that does not value the public good will not advocate policies that reduce social and economic inequality.

Looking backwards

While writing this post I wondered why I had failed to see all along how interconnected my ideas were. Just as I was finishing, though, I came across a reassuring thought. It was in an essay by a medical student, reflecting on her learning process: “[T]he only stable truth is that which one has struggled for, even if it is something, looking back, we feel we could have known from the beginning.”

Whew! Continued in one final post, part 4, where I look back on my year off, explain why these topics are not simply intellectual interests but are personally meaningful to me, and explain “embracing the abnormal.”

Related posts:

What is healthism? (part one)

What is healthism? (part two)).

References:

Paul Zane Pilzer, The Wellness Revolution: How to Make a Fortune in the Next Trillion Dollar Industry (2002)

Robert Crawford, Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life, International Journal of Health Services, 1980, 10(3), pp 365-88

Richard Hofrichter (editor), Health and Social Justice: Politics, Ideology, and Inequity in the Distribution of Disease (2003)

Trisse Loxley, Designer feet: Women who will do anything to fit into their Jimmy Choos, Elle Canada

Barbara Ehrenreich, Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America (2009)

Benjamin Wallace-Wells, The Romney Economy, New York Magazine, October 23, 2011

David Coburn, Income Inequality, Social Cohesion, and the Health Status of Populations: The Role of Neo-liberalism (PDF), Social Science & Medicine (2000), 51, pp 135-146

Caleb Pressman Gardner, A Moment’s Thought: How to Tell a True Medical Story, JAMA, June 13, 2012

Jan-

I’m not a regular blog reader or web commenter (perhaps you’ve changed my life!), but I was so impressed by the intelligence, passion, and clarity of this essay that I just had to thank you.

I’m a prof., social theorist, feminist, and scholar of neoliberalism, and I found this the clearest, most concise, analytically insightful, and human statement of the interconnections of neoliberalism, corporatism, healthism, and medicalization that i have ever encountered. by far. wow. and thanks.

i’ll be teaching you next week in my big lecture course on Social Problems. i’ll share with my students the link to your work, along with the giant smile i’m now sporting just thinking about how much i like you. very nice to meet you here.

happy spring,

sharon

prof of sociology and gender studies

u. of southern california

Sharon,

Wow, I am honored by your response. Thank you so much.

I am passionate about inequality, the social determinants of health, and the role of neoliberalism in perpetuating inequality and preventing the implementation of SDOH policies. I haven’t posted here in a while and really should get back to this topic. I’ve been reading critical psychology and critical health psychology and thinking about how 20th century psychology changed society in ways that are perfectly in sync with the interests of neoliberalism. I’m also wondering if the psychology angle on neoliberalism might offer opportunities for change (critical psychologists argue for “social action”) that politics does not. I’m almost ready to start a new blog on this topic.

I see you were at Santa Cruz, home of Bettina Aptheker. I have her DVDs, but am not up on feminist theory at all. Friends tell me that my interest in how things like corporatism/neoliberalism/healthism interact may be an example of what feminists call intersectionality (although that may be stretching the meaning of the term).

I will definitely check out your books — The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood

(what a great title!) and Flat Broke with Children.

I really should get back to what I wrote about here. Thanks again.

Jan